The Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF), Glascoed incorporated a housing estate for key workers that presumably was built around the same time as the main ROF site. N.W. kindly shared the following regarding the origins of the Estate:

“Even though we all rented the two- and three-bedroomed houses there was a distinct property hierarchy, at the very top of which came the four larger houses at 1 to 4 West Road, built for military officers, senior managers and their families. The rest of West Road was confusingly set at a dog leg a few hundred yards further down the road. Even more bafflingly, the later Beaufort Crescent was actually more or less a continuation of the four posher houses, but took a different name. The lack of documentation means I can’t say for sure when the houses were constructed. West Road definitely came first, probably in the 1940s when the factory itself was built during the war. I have a vague memory that Beaufort Crescent dated from around 1952, but the link to the start of the Elizabethan age was probably coincidental. Despite the Crescent’s more hifalutin name, it was definitely regarded as the poor relative – the (comparatively) cheaply made and pebble-dashed newcomer.“

Facts and Figures

Year of Construction

c. 1940s.

First Recorded Residents and year

Not known.

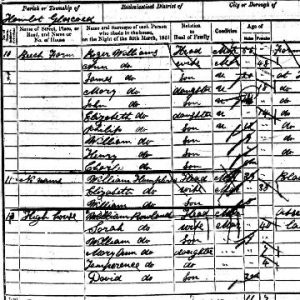

Residents at time of the 1851 census

The site was farmland belonging to one of the Wernhir farms in 1851.

History

For the fuller history of the Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF), and the Wernhir farms that it took over, please see the following pages:

As mentioned above, the first houses (West Street) were probably built in the 1940s and the second part (Beaufort Crescent) was built circa 1952. The houses were built to accommodate managers and key workers along with their families.

Location

This 1971 map of the Estate, has been used with permission from the National Library of Scotland’s marvellous “Old Maps” section.

A clearer image can be found on the National Library of Scotland’s website.

Living at ROF Glascoed in the 1970s.

An account written and kindly shared by N.M.

The past of the residential ROF estate in Monkswood seems to have been wiped from history – or rather, it never really made the leap into digital history. All that remains are the estate agents’ pictures on Right Move, showing the gradual rise in house prices since they first appeared on the market (back in 1998, it seems). At that point they were worth around 45,000 pounds, now it’s more like £250,000, depending on the level of desirable ‘features’. The estate is not mentioned at all on the ROF’s Wikipedia page. It’s as if we never lived there at all.

Even though we all rented the two- and three-bedroomed houses there was a distinct property hierarchy, at the very top of which came the four larger houses at 1 to 4 West Road, built for military officers, senior managers and their families. The rest of West Road was confusingly set at a dog leg a few hundred yards further down the road. Even more bafflingly, the later Beaufort Crescent was actually more or less a continuation of the four posher houses, but took a different name. The lack of documentation means I can’t say for sure when the houses were constructed. West Road definitely came first, probably in the 1940s when the factory itself was built during the war. I have a vague memory that Beaufort Crescent dated from around 1952, but the link to the start of the Elizabethan age was probably coincidental. Despite the Crescent’s more hifalutin name, it was definitely regarded as the poor relative – the (comparatively) cheaply made and pebble-dashed newcomer.

My parents moved there in the early 1960s after the closure of ROF Pembrey. The estate was technically reserved for those who might need to get to the factory quickly in an emergency: mostly firemen and policemen (for they were invariably men) who worked shifts, but also some technicians, the managers of the social club, and so on. The factory’s day workers who actually produced the bombs were bussed in from nearby towns or drove from the surrounding villages.

By the 1970s there was a definite sense that the ROF had passed its heyday: retired workers were allowed to remain in the tied house if they wished, and the two tennis courts at the social club were no longer maintained, until at some point the net sprang more holes than would usually be advised and weeds grew unchecked on the concrete surface. Despite the decay, the Cold War was at its height back then, and we kids were very aware of it. Amidst the general terror of an impending nuclear bomb – the main question was not if but when it would hit – there was a sense of relief that at least we would all be killed instantly at the epicentre of a Russian atomic warhead. Only much later did I realise that this was not something young children should even be aware of, let alone find reassuring. People are deceiving themselves when they bleat that children today have lost their innocence at a much earlier age because of social media. We just weren’t supposed to trouble the adults with our fears back then.

In other respects it was the most wonderfully liberated and liberating childhood: we were largely granted the freedom to play among ourselves without adult supervision in the fields and woods. The general expectation was that we should come in for meals or before it got dark. The woods next to the ROF factory were the best playground of all. Berthin Brook wound its way through the trees, although we all knew it simply as ‘the stream’. A more pioneering older generation of kids had installed a rope swing and a treehouse at its central hub, which felt deeply, almost primevally rural although it was no more than a hundred yards from the front gate of the factory.

While the woods and fields were all actually owned by the ROF, they were mostly rented out to local farmers as grazing for cows and sheep. There were at least two abandoned concrete flak towers in the fields, where the naughtier kids would practice their fire-lighting skills with gathered twigs and purloined matches. It never occurred to anyone that we should not be playing there, and as long as we never strayed onto factory premises it was largely tolerated. Since a fair few of the kids involved were the offspring of factory police, their inaction was hardly surprising. I later even wondered if we’d been seen as a convenient informal set of spies, keeping an eye on any strange goings on around the factory (spoiler alert: we never encountered any suspicious parachutists with binoculars).

We were, however, highly aware of environmentally sustainable play before sustainability had even become a buzzword. Armfuls of the abundant wild daffodils and bluebells could be picked in spring and displayed proudly at home as long as their bulbs were not touched. Everyone knew that the rarer primroses were to be left alone. We were voracious foragers ahead of our time: blackberries were picked by the pound in autumn and then frozen – I still find it difficult to accept that supermarket berries cost so much. My dad made some undrinkable wine from local elderberries, and the hazelnut trees lining the lane to Glascoed provided a great snack for those who were prepared to bash a stone down upon them as an improvised nutcracker.

Occasionally there were casualties of the wild play: a broken arm here or toe there. Once an older boy ate the poisonous red tree berries as a dare and had to have his stomach pumped. A look at Google just now has not told me which kind of berry it might have been – whatever it was, we had learned our lesson and kept away from all red berries, just in case. The closest we ever came to actual criminality was an occasional bit of scrumping from those foolish enough to have apple trees in their garden.

The estate had a wooden shack of a community hall, which could be booked for birthday parties, meetings and the like. The mothers ran their own informal nursery there in the mornings for three-year-olds, in preparation for Big School. That amount of childcare was, of course, not designed to enable the wives of shift workers to take paid work. One of the things that bonded us estate children was simply that everyone understood what it was like to have a father who worked very strange hours. At some point in the 1970s new 12-hour shift patterns were introduced that would mean two day shifts from 6am to 6pm, followed by two night shifts, and then two days off. Repeat ad nauseam. The fire station had to be staffed whatever the circumstances so occasionally my father would do paid overtime, involving a 24-hour shift that later required a lot of sleeping off on what was supposedly his free time. We got used to our fathers being around at weird times, away at weekends, asleep throughout the day, or even at work on Christmas Day, although the scheduler tried to ensure that dads with young families weren’t (often) assigned that day shift.

The road to the factory ran past the field in front of our houses; it was largely empty apart from one traffic jam of cars and coaches in the early morning, and another at 4pm, when production closed for the day. That road was the only relatively flat surface around, so it served as our impromptu tennis court. We would each keep an eye out for approaching vehicles and briefly leave the ‘court’ until they had passed. Car stops play.

The biggest recurring special event of the year was probably Bonfire Night, on 5 November. Now that I live in a different country and am married to a Catholic, it seems preposterous that we celebrated someone being burned at the stake three centuries ago as a family-friendly occasion. But it had nothing to do with religion, or parliament, or revolution, and everything to do with community, signalling the impending winter and the end of the outdoor season. For weeks in advance the older kids would haul fallen branches to the field behind the houses, where a circular patch stood bare year round after many bonfire seasons. The evening itself was supervised by the factory fire brigade, which also bought and set off a series of fireworks. Each rocket or catherine wheel was set off separately, with several minutes between them that only increased the excitement as the fire officers ensured minimum distances and appropriate safety standards. Later in the evening safety took a hike as the bonfire burned low, the fire brigade departed with their engine, and we all stuck potatoes on sticks in the embers to bake.

The biggest one-off occasion was undoubtedly the Silver Jubilee in 1977. This was celebrated everywhere in the country, but nowhere more so than on a government estate where societal non-conformists were rare. It was held on the ‘front’ field this time, and involved the usual outdoor tables for a communal meal, sports events for the kids of the egg-and-spoon kind, pony rides (obviously without hard hats!) and a demonstration of the fire brigade’s hosepipe firing skills. I remember it as a high point not only of my childhood but also of the ROF estate. A high point suggests a downward trajectory has to follow, and that certainly seemed to be the case in my memory of the estate.

In the early 1980s we went to the woods one day in daffodil season only to find that the clearing where they usually grew had been torn apart by a construction vehicle, presumably belonging either to the local farmer or to factory contractors. Many of the bulbs had been destroyed or dug up. We kids and mums had spent years ensuring that the site was preserved, that we only took a small proportion of the flowers each time and left the bulbs intact – and it had all gone in a few minutes of officially sanctioned activity. I hope they have grown back at some point since then.